Capital Issues: How the City is failing UK tech – and how to fix it

New joint report from Onward and the Tony Blair Institute

“As leaders of some of the UK’s most successful emerging science and technology businesses, we know only too well the obstacles and difficulties that are being experienced by growing British companies. One of the most pressing reasons for these is the UK’s capital markets. Put bluntly, its public markets are not fit for purpose. Bold reform is needed – and needed now…The government should look seriously at this report.”

The words of six UK tech leaders, endorsing our new joint report report with the TBI, published today, and covered in the FT.

Failing to capitalise

The City of London is in trouble. Last year 76 firms delisted from AIM, London’s growth market, and scores of leaders of the UK’s most vibrant companies have publicly stated that they would not consider listing on London’s exchanges. Over the past ten years the value of the S&P 500 (the index of the top 500 companies listed in the US) has grown ten times faster than the UK’s FTSE 100.

Growth in the S&P 500 has outstripped the FTSE 100

Source: Curvo

Decline isn’t inevitable. There’s a huge opportunity for the UK. Europe now has over 1,500 startups generating over $25 million in annual revenue, and more than 250 are generating $100–500 million – almost half of which are UK-based.

But we can’t rely on US markets to endlessly capitalise these scaling companies. European companies tend to struggle after listing on US stock markets, with European firm listings in the US seeing their share price fall by an average of over 70%.

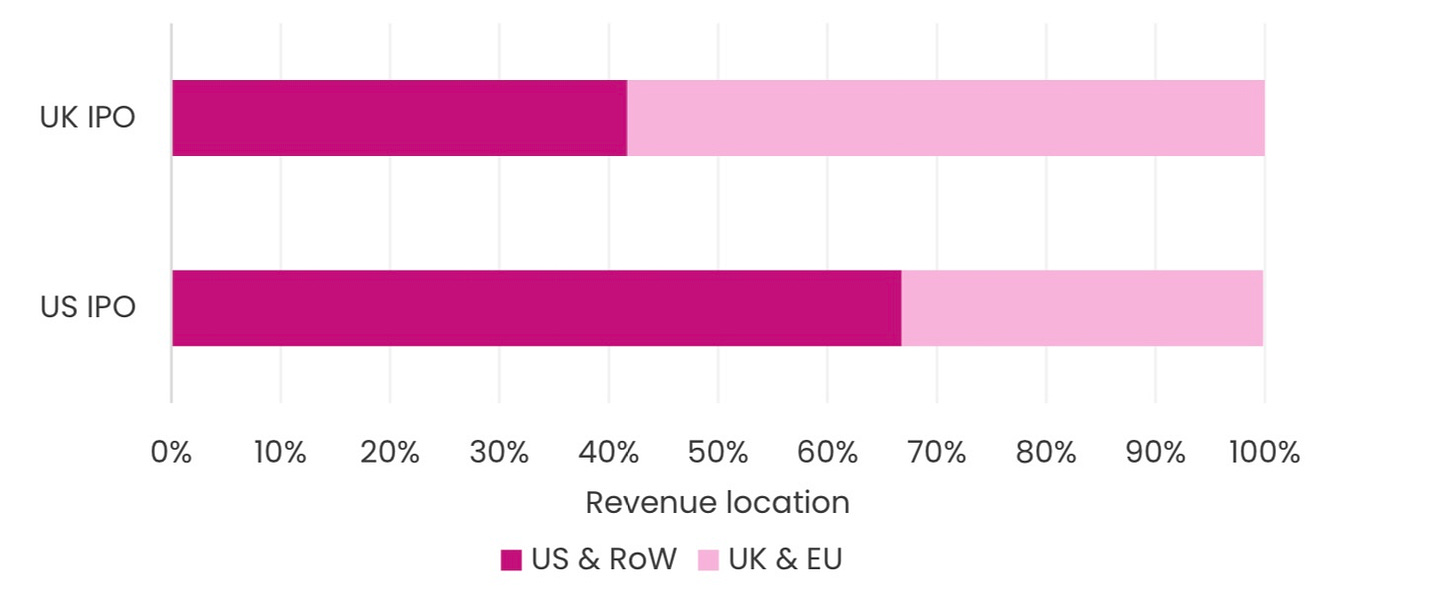

And the average UK company that lists in the US gets most of its revenue from there, which is not the case for most UK companies.

UK firms that list in the US tend to have significant revenue outside the UK and Europe when they IPO

Source: Company IPO filings analysed by Onward/TBI

So the UK (and London) can’t rely on the US riding over the hill.

Rewriting the narrative

Fixing London’s capital market issues won’t be easy. Many have misdiagnosed the problem. They argue there is a lack of capital for the UK’s largest companies: if only they had more investors, share prices would rise and the issue would be solved.

Instead, it has been the UK’s historic inability to modernise and support high-growth tech firms to scale that has been the ultimate source of the City’s decline.

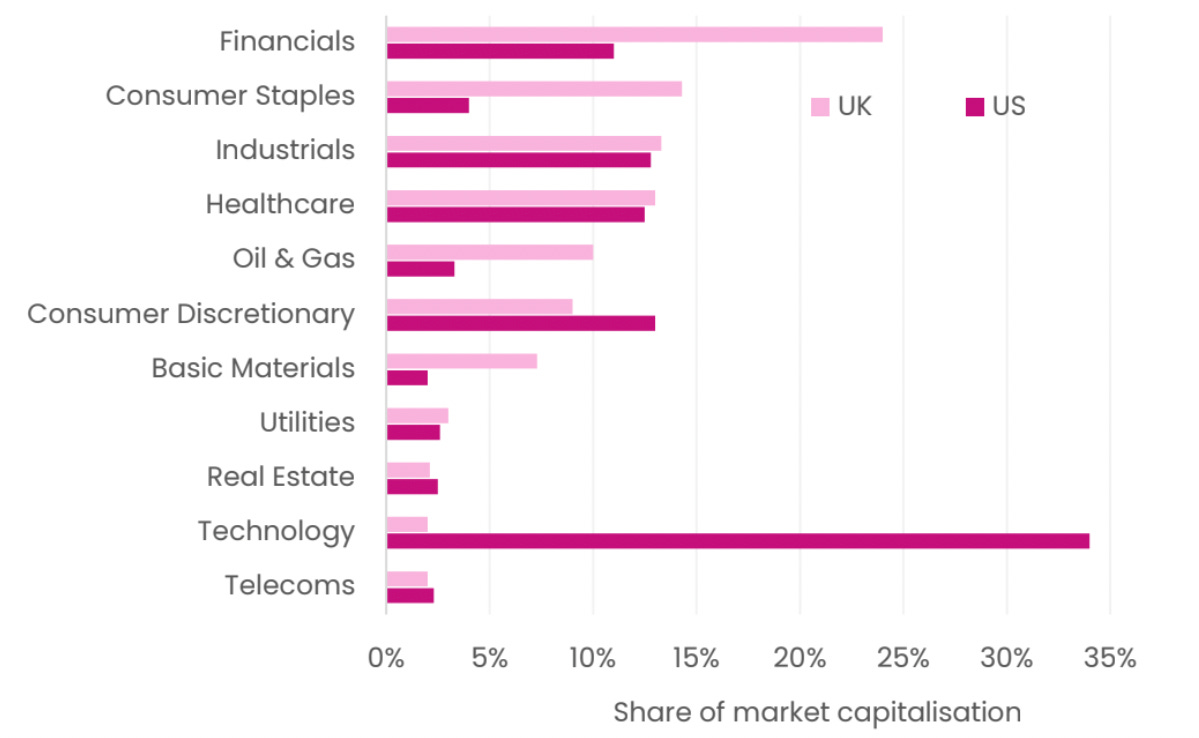

This has left UK public markets overly reliant on firms from established, slow-growth sectors such as finance, oil and gas – unlike the US, which is far more technology-focussed.

UK public markets over-represent financial-services firms and under-represent technology companies compared to the US

Source: Panmure Gordon, shared with TBI and Onward

Large technologies are responsible in large part for the overperformance of the S&P 500 relative to the UK. Without the “magnificent seven”, there have been long recent periods where the S&P 500 has actually traded at a lower price-to-earnings ratio than the FTSE 100.

How big tech companies (the “magnificent seven”) boost the S&P 500 compared to the UK’s FTSE 100 (2018–2024)1

Source: Factset

How the UK stymies scale-ups

The problem, therefore, isn’t that the UK’s biggest companies don’t have enough money. It’s the underlying factors that make the UK’s capital markets unsupportive of the high growth firms of the future. There are three key challenges behind this.

1. Institutional underinvestment: No risk, no reward

The UK’s pension and insurance industries underinvest in UK equities compared to others. On the private side, in the US, pension fund investments make up around two-thirds of the venture capital sector; in the UK they make up just 10%. As we argued in our Pension Power report, pension funds need to step up their investment in venture capital to resolve this gap.

For public equities, defined benefit (DB) pension assets have withdrawn markedly from UK equities in public markets. Regulatory and demographic changes have shifted these investments toward low-risk, fixed-income assets, starving innovative and high-growth sectors of capital.

Pension capital is retreating from UK equities

Source: FTNew Financial

2. Small funds, big problem

Next, the UK doesn’t just need more investors. It needs more of the smaller investment funds that typically invest more in small- and mid-cap firms. But over the last 15 years, the proportion of small UK investment funds has halved.

Meanwhile, passive investment strategies (which allocate capital to indices rather than individual companies) are now almost 40% of global investors, further reducing the amount of capital available for smaller firms not included in major indices like the FTSE 100 or FTSE 250.

The rise of passive investment in the market (2013–2022)

Source: Peel Hunt

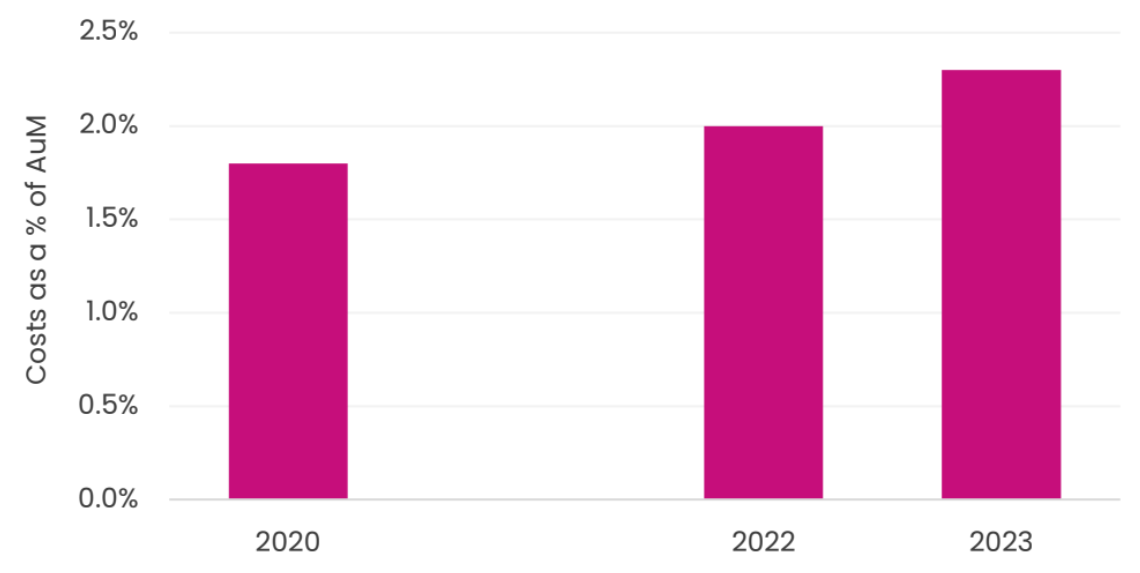

This decline has been exacerbated by overregulation. Compliance costs associated with the Senior Managers and Certification Regime, the 2020 Stewardship Code, and anti-money laundering (AML) regulations have made it far more expensive for smaller funds to operate. The UK’s compliance costs are particularly high: AML regulations alone cost UK businesses six times more than their US counterparts, totalling £38 billion annually. Fewer small asset managers means less money for IPOs and for British tech companies.

The cost of anti-money-laundering measures has increased significantly for smaller asset managers

Source: Oxford Economics

3. The AIM is off: Why public listings are unattractive

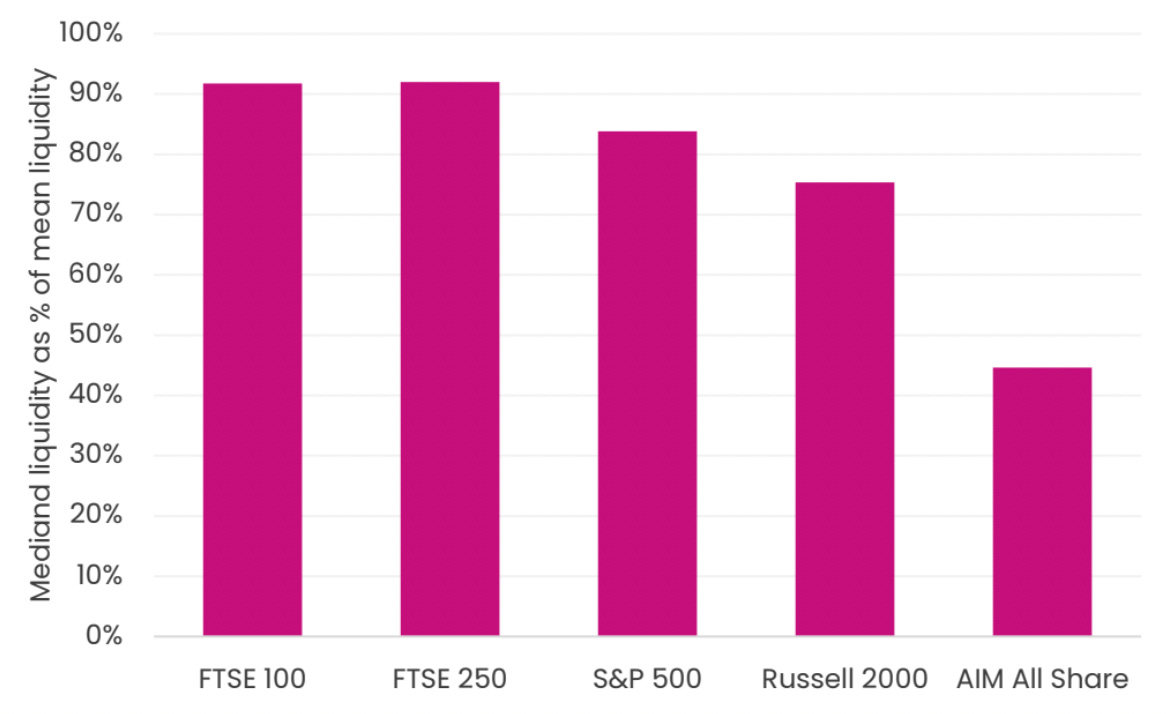

Lastly, the public listing environment in the UK has become increasingly unattractive for small and medium-sized companies. This is caused by low liquidity, minimal professional analyst coverage, and a lack of investor interest.

AIM, the UK’s growth market for small and medium-sized firms, has particularly struggled. The average medium-sized AIM-listed company has just a quarter of the analyst coverage of the Russell 2000.

In part as a consequence, the average AIM-listed company has very low liquidity – far lower than the mean across the entire market. This is especially bad for those outside the top – a consistent refrain by CEOs and others we spoke to.

Liquidity on AIM is far less evenly distributed than on the FTSE 100 or S&P 500

Source: BloombergFTSE 100, FTSE 250, S&P 500, Russell 2000, AIM All Share

Without analyst coverage, companies struggle to attract investors, further diminishing liquidity and making it harder for firms to grow. It also frequently takes longer than four months to list on AIM according to institutions and advisors, far longer than the six-week timeframe for the Nasdaq.

Rewriting the rules

London’s exchanges need radical transformation. First, AIM must be closed, and a fast-track listing process should be created on the LSE Main Market. High-growth tech companies should be able to list with time-limited tax and regulatory benefits similar to those currently offered by AIM. This will help London differentiate itself from other global exchanges and attract a new generation of innovative companies.

Second, the government must take advantage of the London Stock Exchange Group’s planned PISCES platform – an intermittent trading venue for private companies – by ensuring it’s focused on pre-IPO investment. This would involve de-risking investments and attracting institutional capital to growth firms and IPOs.

Third, the UK’s investment ecosystem needs to be expanded and upskilled. The government should earmark £1 billion to invest in five growth-focused venture funds, crowding in institutional capital and creating a new generation of large-scale growth investors. The Government should make an advance market commitment to support equity research.

Finally, regulatory burdens must be reduced. The compliance and governance costs associated with being an asset manager or listed company must be streamlined to encourage greater active investment in equity markets.

Successful reform could unlock the UK’s potential to produce the first trillion-dollar European tech company, foster innovation, and secure our economic future. We must seize this opportunity or risk falling further behind.

Read the full report here.

Note: Average P/E (NTM) refers to the average price-to-earnings ratio based on earnings from the last 12 months. Ex. Mag 7 means excluding the magnificent seven (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla.