British politicians often blithely say they want us to be a science superpower, but they’re failing to face reality.

Mistakes are still being made especially on how we’re approaching the five frontier technologies. We talk a good game on everything from AI to quantum, but we need to be more honest about what can be done. In short, Britain can’t be world leading in all aspects of every frontier technology.

In an upcoming Onward report Future Frontiers, Allan Nixon and Anastasia Bektimirova argue that the UK can use these new frontier technologies to bolster its national standing, but our current approach needs rethinking.

We’re trying something different with this paper, publishing it in digestible chunks to set out our findings and recommendations for each of the five technologies. But first, let’s look at the problem, why leadership matters, and how it can be fixed.

Welcome to the new frontier

Why should the UK bother to lead in frontier technologies?

Countries that lead in these technologies will be both more prosperous and secure. Leading means turning insight into power, but the UK still performs poorly at turning these strengths into economic success and military advantages.

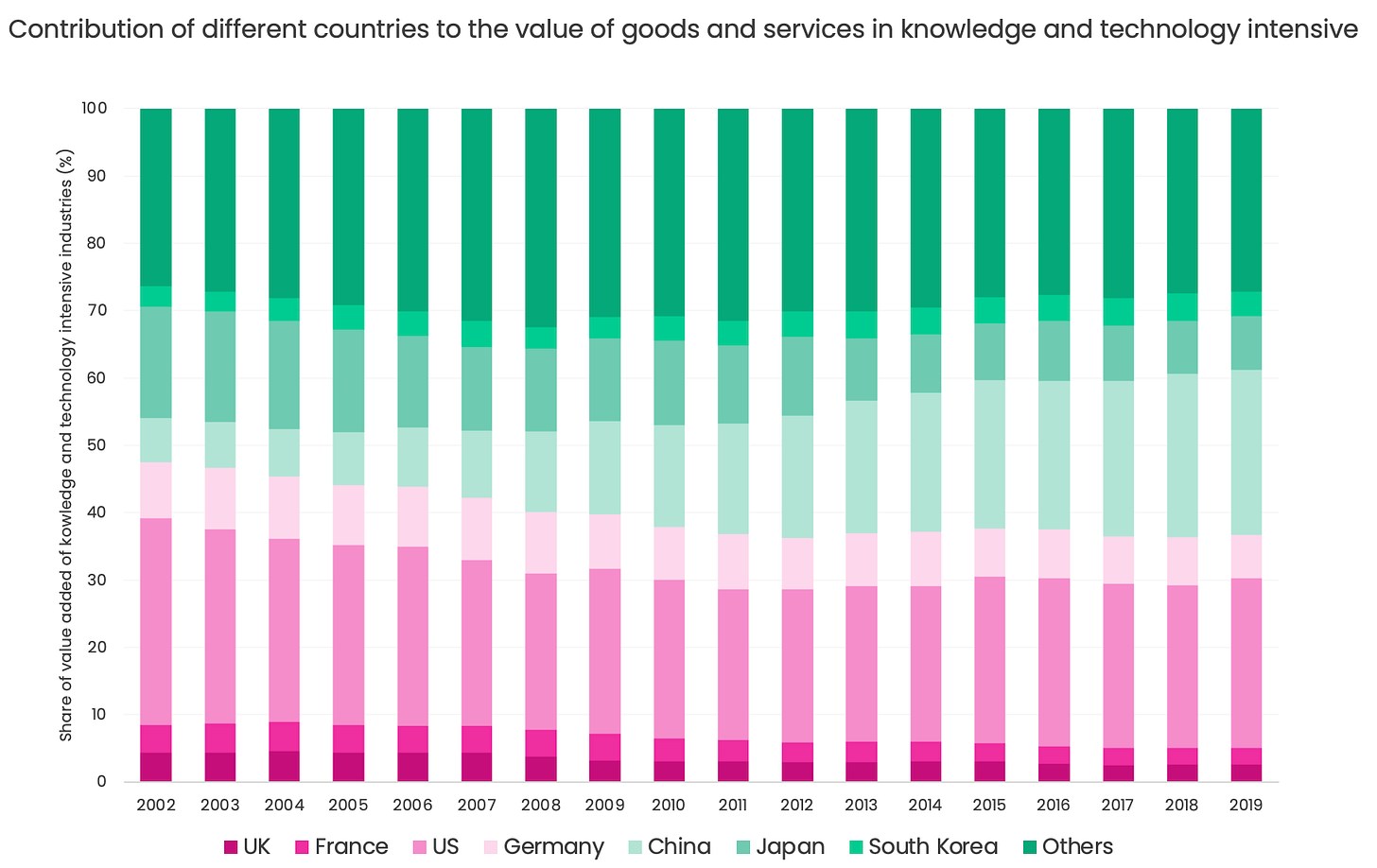

While the UK’s R&D expenditure makes up around 5% of the world’s R&D resources,1 its share of global value-added output from R&D-intensive industries has decreased steadily to 2.6%.

Crudely, it is getting out half of what it is putting in compared to the rest of the world.

The UK is also falling behind other countries. Even in areas where the UK is still strong, such as pharmaceuticals, its global market share has halved in recent decades.

Meanwhile China’s has increased five-fold:

If urgent action isn’t taken, the UK is going to lag even further behind its rivals.

As frontier technologies grow in importance, picking and finding ways to secure strategic advantage will be ever more crucial.

The problem

To have any kind of leadership in this arena, the UK must choose the specific areas where we can and should lead.

We need to invest in public goods and get out of the way to unlock private enterprise. But too often, we fail to do this.

1. We’re not choosing properly

Momentum has been gained in recent years with science and technology, but the Government’s approach still isn’t right. The Integrated Review three years ago set “sustaining strategic advantage” as a core national objective by turning the UK’s science leadership “into influence over the critical and emerging technologies that are central to geopolitical competition and our future prosperity.”

And last March, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology was born — focused on leveraging strategic advantage in five priority technologies: AI, quantum, engineering biology, semiconductors and future telecoms.

But the concept of “owning” a technology, according to its Own-Collaborate-Access framework, is unclear. Arm, for example, is a world-leading chip design company headquartered in Cambridge. But it was bought by a Japanese investment bank (Softbank) in 2016, and in 2023 it listed on a foreign stock exchange, the NASDAQ. Is that British owned?

Even owning these technologies is not tied to achieving specific outcomes. The Government’s five priority technologies are underpinned by action plans, but none explain for what ultimate purpose the UK plans to build strategic advantage.

The Government continues to spread its investments instead of making bold, calculated bets. The UK cannot compete at the scale and breadth of the US or China. Building a world-leading edge requires a level of focus which we currently lack.

Take quantum. The Government announced £70 million for quantum to “ensure the UK becomes a world-leader” and “solve global challenges” such as helping to speed up diagnosis of cancer. But this was spread across 38 separate projects, meaning an average of less than £2 million per scheme.

More recently, £80 million was announced to launch nine AI research hubs. But the entire investment is barely enough to cover the costs of training a single state-of-the-art Large Language Model such as GPT-4.

And the Government can’t even assess if its strategy is effective. It’s not clear that research funding is being optimised for building strategic advantage through translating research into tangible impact.

2. We’re not targeting investment

The Government is spending record sums on R&D, but not on the critical capacity needed. Funding by governments past has been disproportionately focused on supporting basic research through academia over applied research such as publicly-funded labs similar to Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes.

The result is a public research sector that is ill-equipped to drive the state's strategic priorities and deploy technologies into the economy.

The creation of the Catapult Network – centres promoting R&D and innovation through business-led collaboration across academia, Government and industry – was an attempt to address this, but the Catapults are still underpowered.

The Network is modelled on Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes, but they receive eight times the funding.2 And there are gaps in the Network too, with no Catapult focused on quantum technologies.

In manufacturing, other G7 nations are reshoring capabilities and rebuilding domestic know-how. Yet the UK languishes. It has seen the largest comparative decline of goods exports of all the G7 nations since 2018.

In engineering biology, there are the funds but not the space. Cambridge is a global biotech hub, which will likely benefit from a significant proportion of the Government’s £2 billion commitment into engineering biology.

But lab space in Cambridge is in cripplingly short supply, with a deficit across Cambridge and Oxford of two million square feet.

3. We’re not getting out of the way

Often the Government needs to play an active role in spurring innovation, but other times it needs to set the conditions then step back. But again, there are issues. The UK’s tax incentives for science are riddled with problems. Its R&D tax credit scheme is the costliest in Europe, but is poorly administered, with an estimated £1 billion in error and fraud, and businesses are struggling to get approval, leading to the Government recently announcing action to tackle this.

And previous Onward research shows the UK is out of step with other countries when it comes to focussing our R&D on national priorities, preferring instead to support through less targeted tax credits.

Regulators are also causing blockages. In engineering biology, UK novel food companies such as Hoxton Farms are globally renowned. But the FSA’s Chief Executive has openly admitted not being able to keep pace with novel food technologies due to resource constraints. And the MHRA is assessing just 26% of clinical trial applications in 30 days in 2022-23, against a target of 98%.

The overall result is muddled. We don’t have a good understanding of what our capabilities are, where we should be focussing our future efforts, and how to strengthen our hand.

The need for a niche

So, the UK must better set its goals for the frontier technologies.

First, it needs a proper definition. “Owning” a technology, in a basic sense, means possessing dominance or leadership that can be exploited by the Government for specific ends.

What are those ends? They boil down to prosperity – growth, productivity, jobs – and security – through military, energy, cyber and climate.

For these ends, the UK should be the best place in the world to develop and deploy elements of frontier technologies. That means:

Leveraging niches. The Government should give targeted support to areas where there is the potential for an outsized benefit. That requires a deeper understanding of the international science and tech landscape.

Investing in public goods. Industrial strategy is often interpreted as greater use of subsidies – this need not be the case. The Government needs to invest in the public goods needed for public-private collaboration in frontier technologies, such as skills development, building key institutions, and improving infrastructure.

Unlocking private enterprise. The Government needs to create the right pro-enterprise conditions, such as a pro-innovation regulatory environment, mechanisms to drive private sector investment in R&D such as tax incentives, and setting the right pathways for skilled migration to enter the UK to work at its top labs, companies and institutions.

In each of these areas, we need to do better. The UK’s prosperity, security and status depend on it.

In the coming days, we’ll be looking at how the Government should tackle each of the five priority technologies – where it should focus, where it should invest, and where it needs to get out of the way.

Global R&D has reached nearly $1.7 trillion according to UNESCO. UK R&D expenditure in 2021 (the most recent year for which there are ONS figures), was £66.2 billion, in USD: $83.6 billion = 4.9%

The Fraunhofer institutes had an annual budget of close to £2.5 billion in 2022 (annual budget of €2.9 billion converted to GBP at the £1 = €1.16633 rate), whereas UK Catapult funding is just £1.6 billion over 5 years.