Britain once led the world in telecoms. Two English inventors developed the first commercial telegram, leading to the world’s first public telegraph company – which would evolve into British Telecom. Later, Scottish extraordinaire Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone.

But today, Britain isn’t the pioneer. Only five years ago, Chinese tech firm Huawei was on the verge of sweeping across UK mobile networks. Were it not for a noisy backbench MP rebellion forcing the Government to reverse its approval, things today could be very different.

Scarred by the Huawei saga, Government thinking on telecoms has evolved. Huawei tech is being removed from Britain’s 5G networks. Ministers have marked ‘future telecoms’ as one of the five priority technologies where the UK should build strategic advantage – quite the reversal.

But is this the right approach? Is it even possible to catch up? As we’ve argued before, the UK can’t lead in all frontier technologies. We need to pick the critical niches where we can lead, invest in public goods, and get Government out of the way to unlock private enterprise.

A lifeline, not a landline

Telecoms aren’t simply the old landline phone your parents insist on keeping. They underpin everything in a modern economy and are critical to national security. Telecoms are fundamental to innovation and new technologies, from building the smart grids needed for net zero to steering the safe operation of driverless cars. The rollout of 5G alone is expected to add $1.3 trillion to the global economy by 2030.

But with dependence comes vulnerability. Last year alone, British businesses lost over 50 million hours and £3.7 billion due to simple internet failures. In 2023, about 440,000 UK households had broadband speeds of less than 10 Mbps – just enough to send emails – while at least 25 Mbps is needed for home working. And the threat can be far more sinister. Rival nations could use anti-satellite technologies to disconnect Britain, shutting down our economy and knee-capping our security infrastructure.

Knocking it for 6?

At the telecoms frontier, the Government’s Wireless Infrastructure Strategy looks to gain an advantage in 6G (the successor to 5G cellular tech) with £100 million of public investment and new hubs. But Britain isn’t set to pioneer the next generation of cellular tech.

Yes, we are influential in research: between 2005 and 2020, we ranked third for 5G publications. Britain is also the European leader in 5G-focused start-ups and scale-ups.

But we’re far behind in private-sector investment in telecoms R&D. In 12 years, British businesses have invested just over half of what South Korean tech giant Samsung spent on R&D last year alone.1

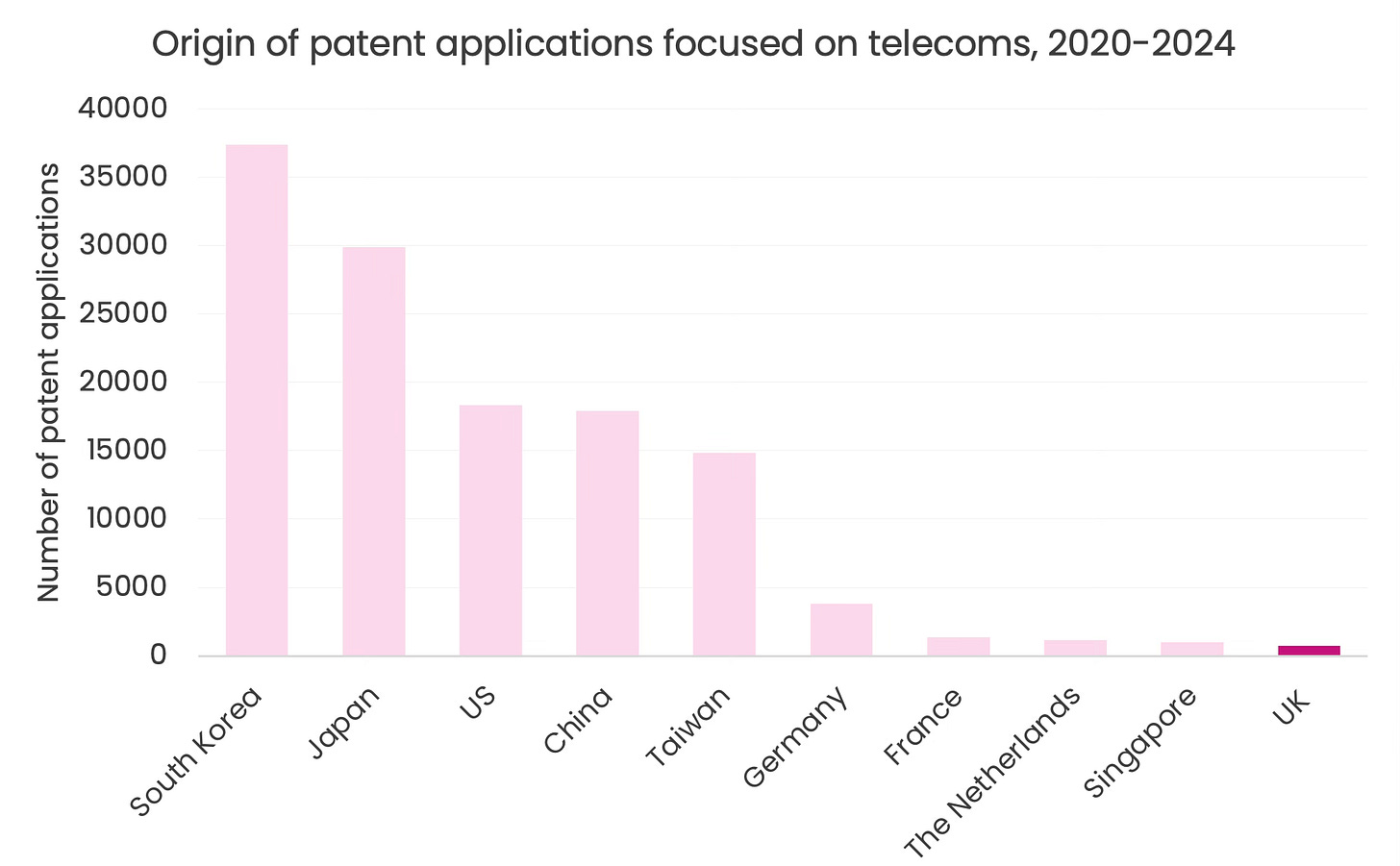

There’s also little evidence that we’re good at commercialising cutting-edge telecoms breakthroughs. Since 2020, nearly 50 times fewer patents emerged from the UK than from South Korea, 40 times fewer than Japan, and 5 times fewer than Germany.

And on 6G patents specifically, it’s nigh-on impossible for Britain to keep pace. China is responsible for four in ten 6G patent applications, while over a third are American. Europe trails wildly behind, with less than one in ten.

British firms have also sold less than £10 million in exports of telecoms equipment in any year for a decade. Contrast this with the UK’s exports of compound semiconductors from its cluster in South Wales, which was over £500 million last year.

Leadership doesn’t come cheap. China has fuelled Huawei’s global rise with a whopping $75 billion in tax breaks. The European Commission estimates that at least €174 billion is necessary to meet Europe’s 2030 connectivity goals.

If Britain were to seriously attempt to run the 6G race, it’s not even clear that it’d be worth it. 5G technology already provides the extremely high speeds and low latency needed for driverless cars, telemedicine, and devices connected through the internet, known as the Internet of Things. 6G might be offering diminishing returns, and it’s unclear what will spark its widespread adoption.

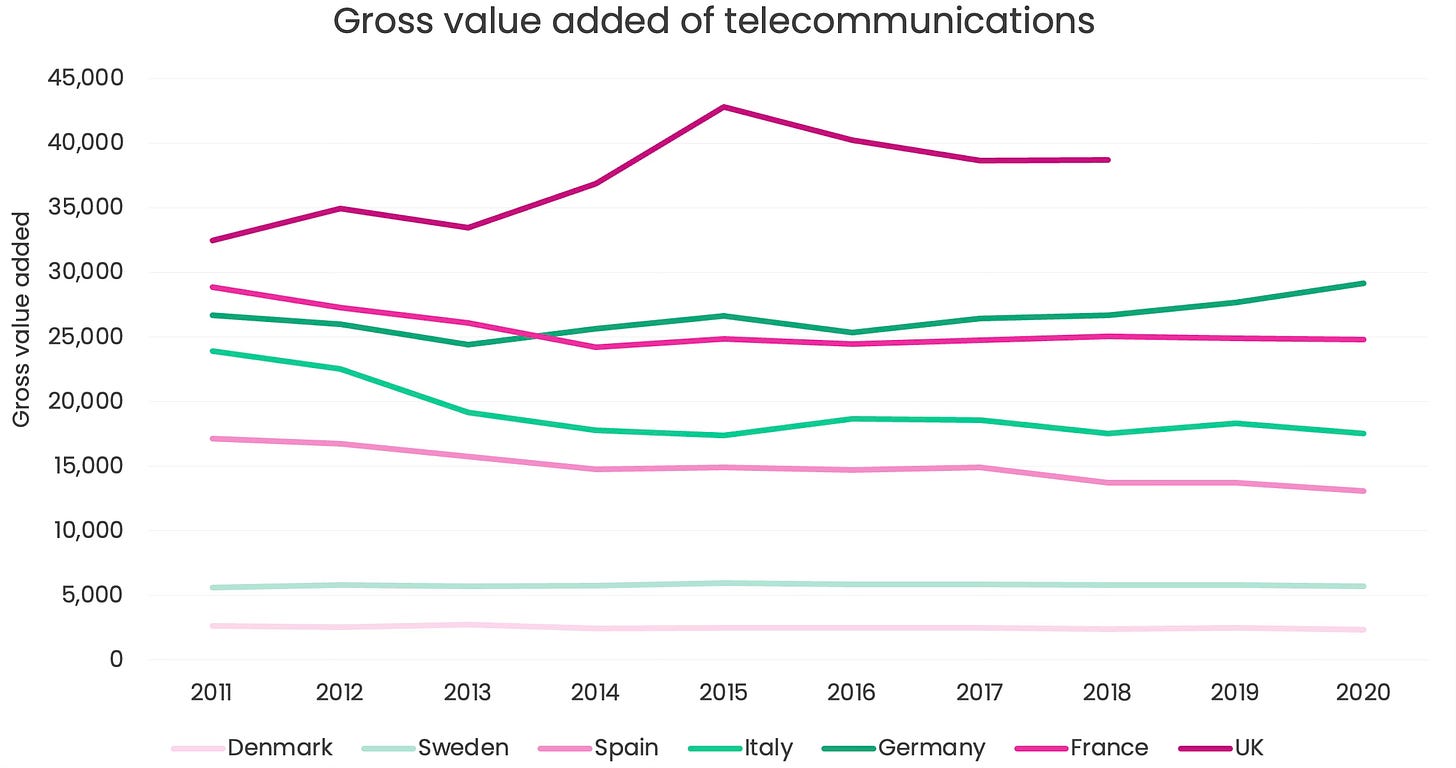

Telecoms, more broadly, is also a low-growth industry, especially in advanced economies.

Satellites

However, satellites – a distinct area of telecoms – could be the area Britain should seek to lead in. The global market is expected to reach $160 billion by 2030. We already host several leading satellite manufacturers that are notable players in the industry and have exceptional space clusters, with over 100 space companies at Harwell alone.

The ground station technologies which connect satellite communications with terrestrial networks can also support lunar and deep space missions with unique capabilities, enhancing Britain’s space industry and defence.

But this may not best fit within the UK’s future telecoms strategy, but instead, our space ambitions. The development, launch and operation of satellites require specialised space technologies, infrastructure, and expertise. A national strategy focused on leveraging our strengths in satellites should exist as part of a broader space strategy.

So what should be our telecoms gameplan?

Setting aside the Government’s misplaced 6G ambitions for a second, the rest of their approach isn’t far off.

Rather than throwing money at “building British champions,” we have largely focused on bolstering telecoms capabilities through international collaboration. We’ve joined a friendly coalition with America, Australia, Canada, and Japan.

This coalition will enhance network resilience, R&D collaboration, information exchange and international outreach. The Future Telecoms UKRI Technology Missions Fund Programme has also been granted £70 million for work with the coalition.

This is a welcome dose of realism. Britain requires a world-class telecoms network, not least to develop a strategic advantage in the four other critical technologies we’ve reviewed. We do need scalable infrastructure that can handle quantum signals, support AI work relying on compute resources in different locations, and ensure seamless data transfers. Britain can’t do this alone.

Ensuring high speed, high capacity and reliable connectivity also means investing in broadband expansion, planning reforms to build and upgrade telecoms infrastructure, and improving cybersecurity. The Government’s upcoming Future Telecoms Vision should focus on these domestic priorities as well as international partnerships.

That’s why the Government should strip future telecoms of its status as a “priority technology”, moving from five areas of focus to four. Ministers should instead focus on ensuring the UK’s telecom network can deploy the latest innovations as quickly as possible.

What next?

Next, we’ll be publishing our last post in this series, looking across the board at the cross-cutting interventions needed to ensure Britain can lead in frontier technologies – particularly how we can continue to attract the best of the best.

UK business expenditure in telecoms R&D from 2008-2020: £12.9 billion. Samsung expenditure on R&D in 2023: $21 billion or £17 billion.