This technology could change everything - if Britain plays its cards right

If you think AI will be the sole disruptive technological force this century, think again.

Quantum technologies may prove to be a game-changer, ones that could revolutionise the digital world as fundamentally as the internet.

Quantum technologies put the power of quantum mechanics — a field of physics studying the behaviour of tiny particles — into practical use, with the potential to supercharge computing, create hack-proof communication, and develop sensors so sensitive they can detect the faintest of signals across the universe.

They may soon solve challenges previously considered unsolvable – quantum sensing for instance provides unprecedented precision, offering breakthroughs in medical imaging, environmental monitoring, and navigation.

But the technology is still nascent. Nations that lead the way will eventually run rings round others, which is why the US enacted laws to stymie China’s quantum capabilities last year. Britain, so far, has a good footing but it can’t go toe-to-toe on every quantum frontier. The Government’s ten year quantum funding of £2.5 billion is generous, yet only a third of what China is ploughing into a single lab.1

As Onward has argued before, Britain needs to focus on niches where it can and should develop a leading edge by investing in public goods and getting government out of the way of private enterprise.

Here’s what we think is needed for the UK to compete in the quantum race.

1. Finding a niche

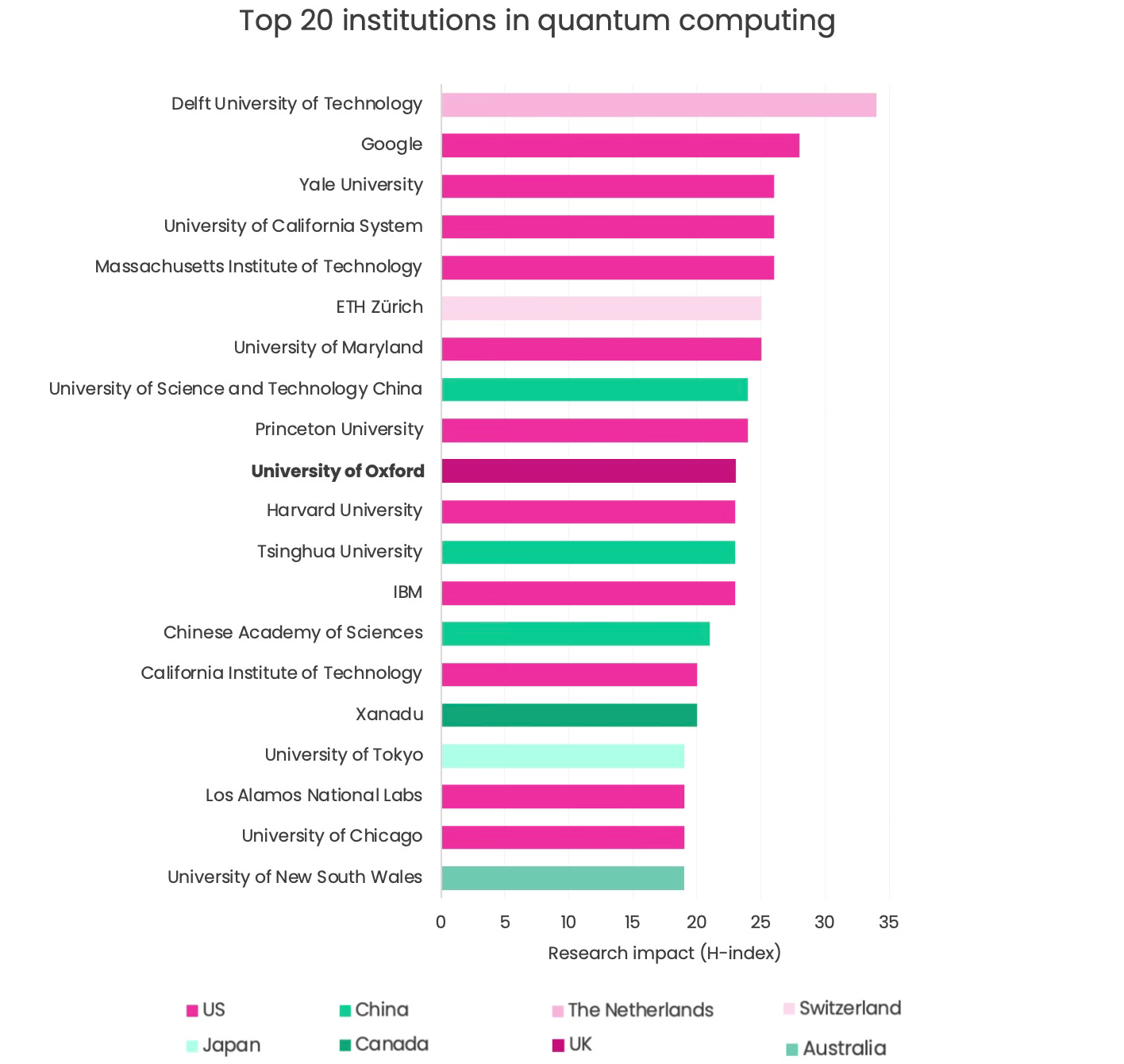

The Government is spreading its bets on quantum technology across five missions, focused on computing, sensing, timing and imaging. But are these right? On the face of it, we’re doing well: Britain’s quantum research ranks third globally and has more start-ups than any other European nation.

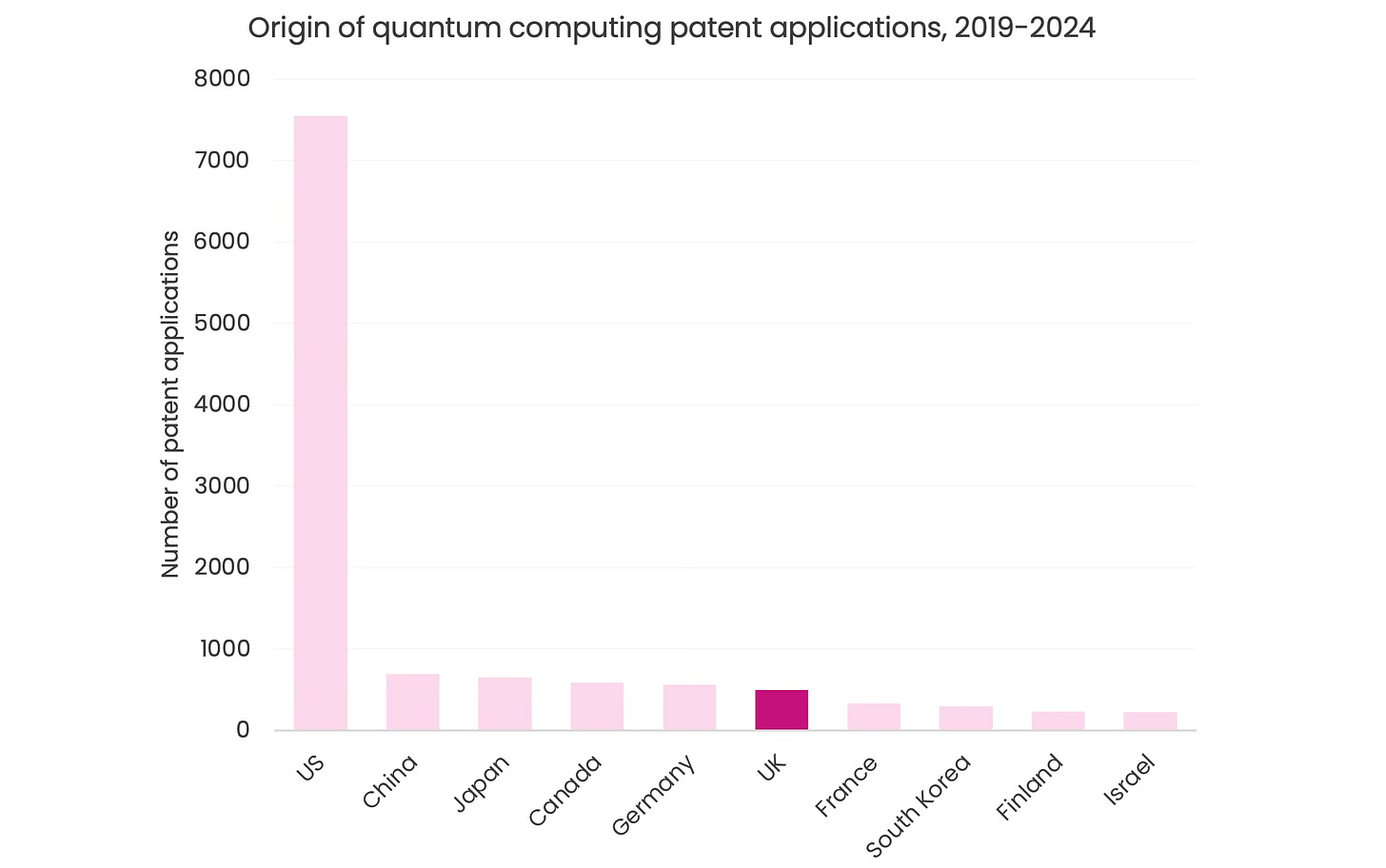

Despite our research strengths and early start-up lead, we’re struggling to be a leader in quantum computing. The UK is behind Germany, Canada, Japan and China on patents registered, with the US way ahead.

Our research on quantum computing isn’t really cutting edge either: it’s all happening in the US and China — with only Oxford University from the UK and a couple of others elsewhere in the top 20 institutions for quantum computing research.

Leading in quantum computing requires a well-developed computing hardware industry. But Britain lacks this, as recognised by the Government’s own Office for Science.

And in the sprint to build a scalable quantum computer – which the Government dreams of – it’s a two-horse race. IBM is investing almost the equivalent of the UK National Quantum Computing Centre’s budget to try to build a quantum computer; other US giants are doing the same. And China is spending $10 billion on a national lab to outpace America.

This is not a race Britain can win.

However, quantum sensing technology is more promising for Britain — this applies quantum physics to revolutionise how we measure, navigate and study the world. Unlike quantum computing, the UK has strong foundations: sensing technology companies already contribute £14 billion a year to the UK economy, employing 73,000 people. Britain’s strengths here are already outsized, with estimates showing it makes up over a tenth of the worldwide quantum sensor industry.

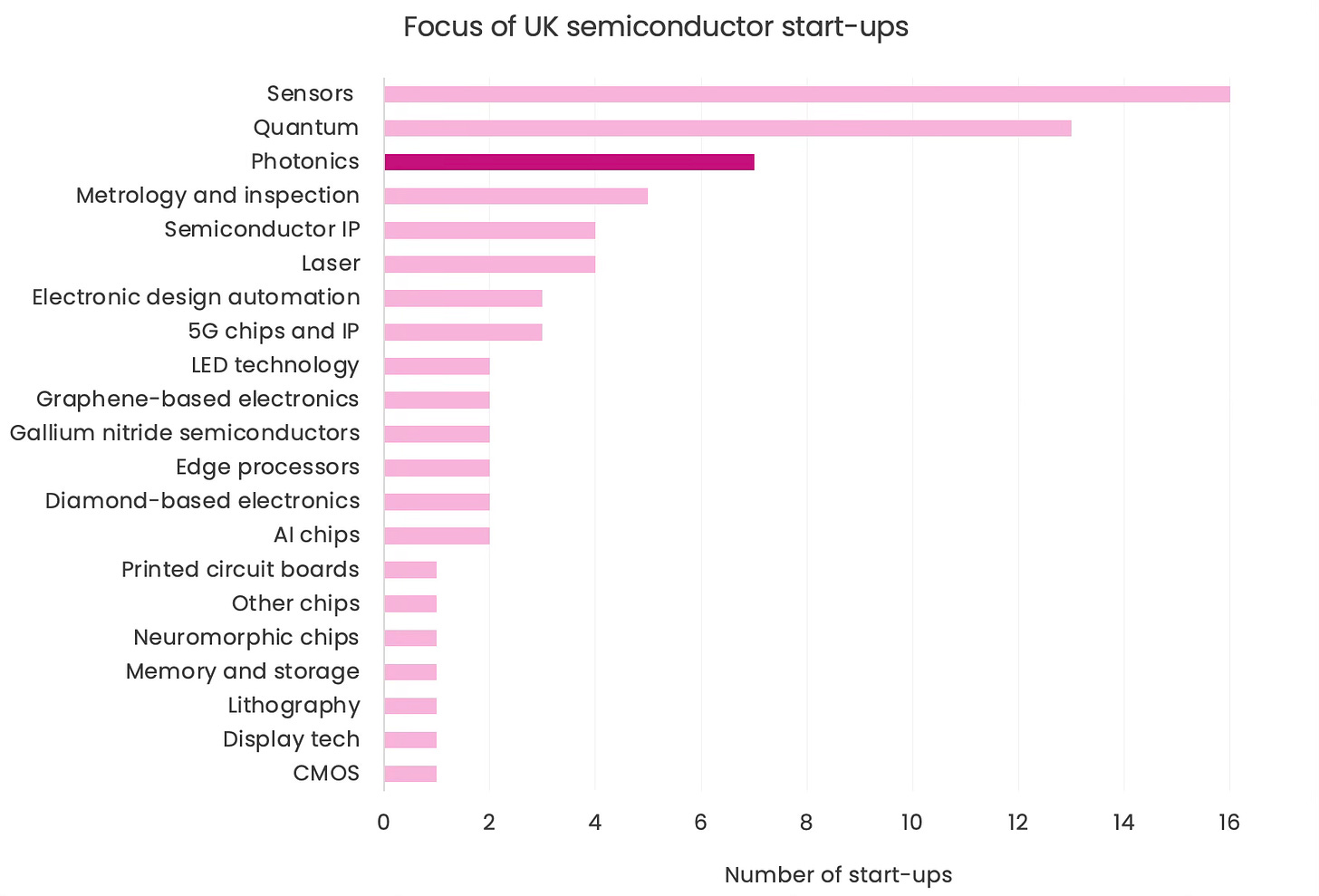

Photonics, a foundational component of quantum, is another opportunity. Up to four-fifths of quantum technologies are estimated to rely on photonics to power them. And focusing on this could be highly lucrative: the global photonics market was valued at $1.64 trillion in 2024, and is expected to increase to $2.25 trillion by 2029.

Britain’s photonics industry employs over 75,000 people and generates more than £14.5 billion for the economy. The photonics start-up ecosystem is also growing.

There’s a particularly strong photonics cluster in Scotland. It already exports 96% of its goods, adding £1.2 billion to the Scottish economy with 60 companies.

Glasgow is also home to the Fraunhofer Centre, a world-leading facility in laser research and development. But its budget is only a little over £1 million a year. If the Government is going to grasp the quantum opportunities available to Britain, it needs to invest more in facilities like this.

2. Investing in public goods

A lack of entanglement

Britain’s quantum infrastructure isn’t ready to deliver. The network of research hubs is fragmented, existing separately instead of having one unifying focus point and research agenda.

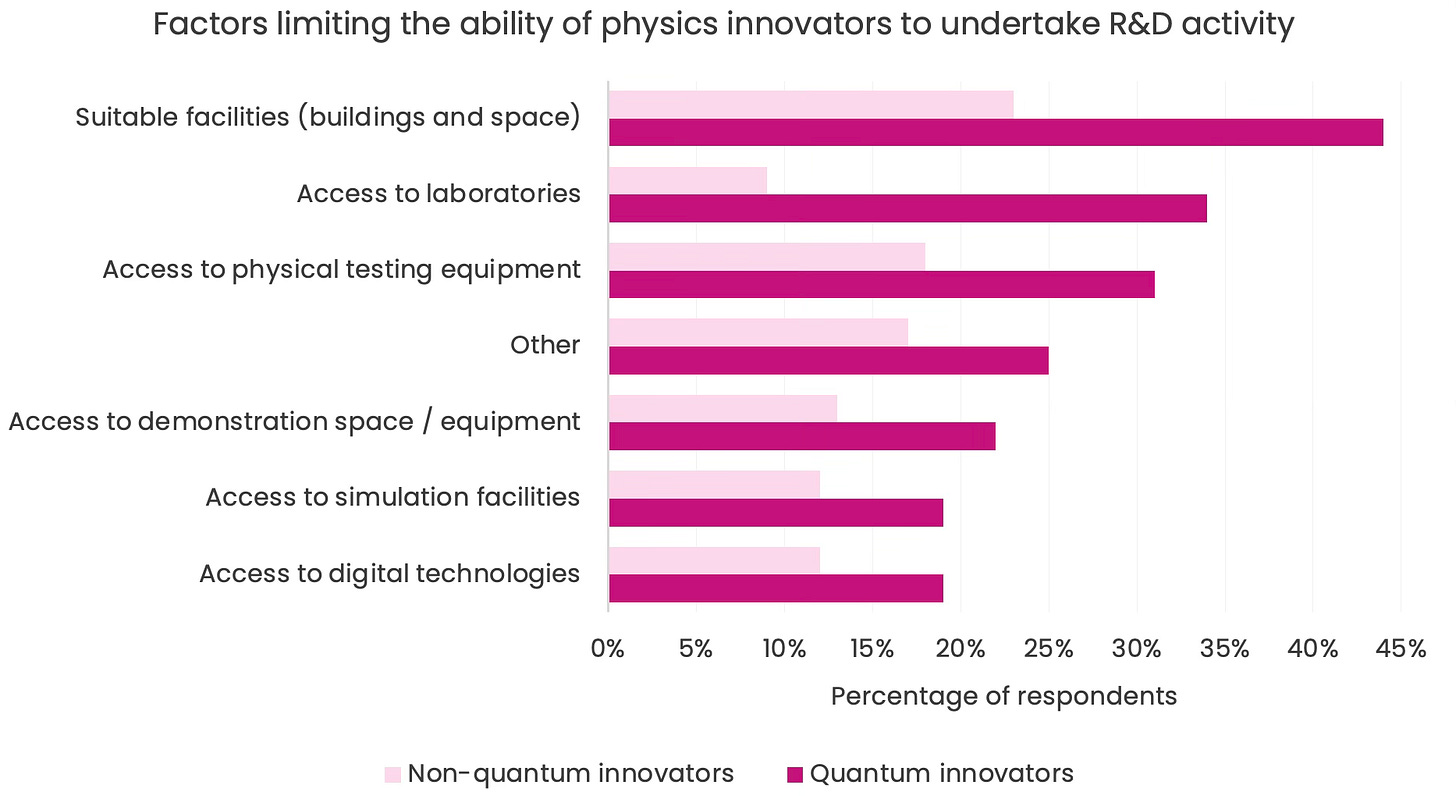

There are also too few facilities such as foundries and cleanrooms critical for quantum, creating a major barrier for industry. Where they do exist, the facilities are often university-affiliated, meaning private firms have limited, costly and often complicated access to them – if any at all.

Quantum foundries are key to commercialisation. These are where quantum devices are manufactured using advanced semiconductor techniques. The South Wales semiconductor cluster may be home to the world’s first open-access quantum foundry but its future is unclear: its grant funding ran out in April 2024 with no more cash in sight.

The availability and access to cleanrooms are another challenge. These are controlled spaces with low levels of pollutants where quantum devices can be built. But the UK lacks large scale open-access quantum cleanroom facilities, with limited sites available in universities and a few other places.

The skills gap requires a (quantum) leap

The other barrier to quantum leadership is a lack of entrepreneurs in the field. The UK may have scientific and engineering expertise, but there are few people ready to take quantum technologies from the lab to the marketplace.

The Quantum Technology Enterprise Centre (QTEC) was working to fill the gap, offering an MBA-style programme to help university researchers become business leaders. A third of Britain’s quantum startups originated here, creating 28 cutting-edge companies and 338 high-skilled jobs. But its Government funding ended two years ago due to a perceived lack of strategic need and budget constraints.

With these challenges in mind, Onward recommends the Government establishment of a new Quantum Technology Catapult with open-access manufacturing capacity and support for entrepreneurial skills.

While the Catapult Network engages in some quantum activities, it does not have a dedicated catapult for quantum. This new Catapult would offer open-access manufacturing facilities, including cleanrooms, and an MBA-style training programme for quantum researchers building on QTEC’s success.

It would not only lower barriers for start-ups by providing resources for prototyping and development but also foster a collaborative ecosystem for researchers and industry, targeting sector-specific challenges to align quantum R&D with national objectives and market demands.

3. Unlocking private enterprise

Quantum interference: Regulate the application, not the technology

It’s too early in the development of quantum to set out a regulatory map. As quantum applications grow, businesses will have to grapple with regulatory requirements. The Regulatory Horizons Councils report earlier this year – welcomed by the Government – set the right course, which the Government should maintain: focus on the application of quantum rather than the technologies themselves, and where appropriate set a clear direction early to give innovators confidence that the UK will welcome experimentation.

What’s next?

Next up we’ll be looking at where and how the UK can build leadership in the third of the Government’s five priority technologies: engineering biology.